A sea of white, gray, and black engulfed the nation’s capital. Kids played in narrow alleyways. Squatting repairmen, cigarettes dangling from the corners of their mouths, pegged away at domestic appliances.

Children scrambled off to school as their footbound grandmothers followed closely behind. Street vendors chanted their slogans and the spice filled aroma of Chinese crêpe wafted in the air.

Men and women of all trades converged for a transient moment, before diverging into their respective work routines and cultures.

It’s the morning rush hour of 1978, a turning point in Chinese modernization. In just a matter of years, overpasses and high rises would dominate the skyline above as torrents of cars vie for leeway below.

Author’s granduncle

Author’s granduncle

Suffice to say, my granduncle was in for a big surprise when he visited the urban U.S in 1978.

There weren’t any city gates marked by their geographic and historical significance. There weren’t single-storied houses that depended on a stove for central heating.

Families were not crowded into a 9 square meter room that didn’t differentiate between living, dining, and sleeping quarters. And the lavatory was not outside the house.

The date was June 1978, and the Chinese Art Troupe had landed in New York, marking the start of a month-long tour of the United States. China was making clear its desire to promote cultural understanding.

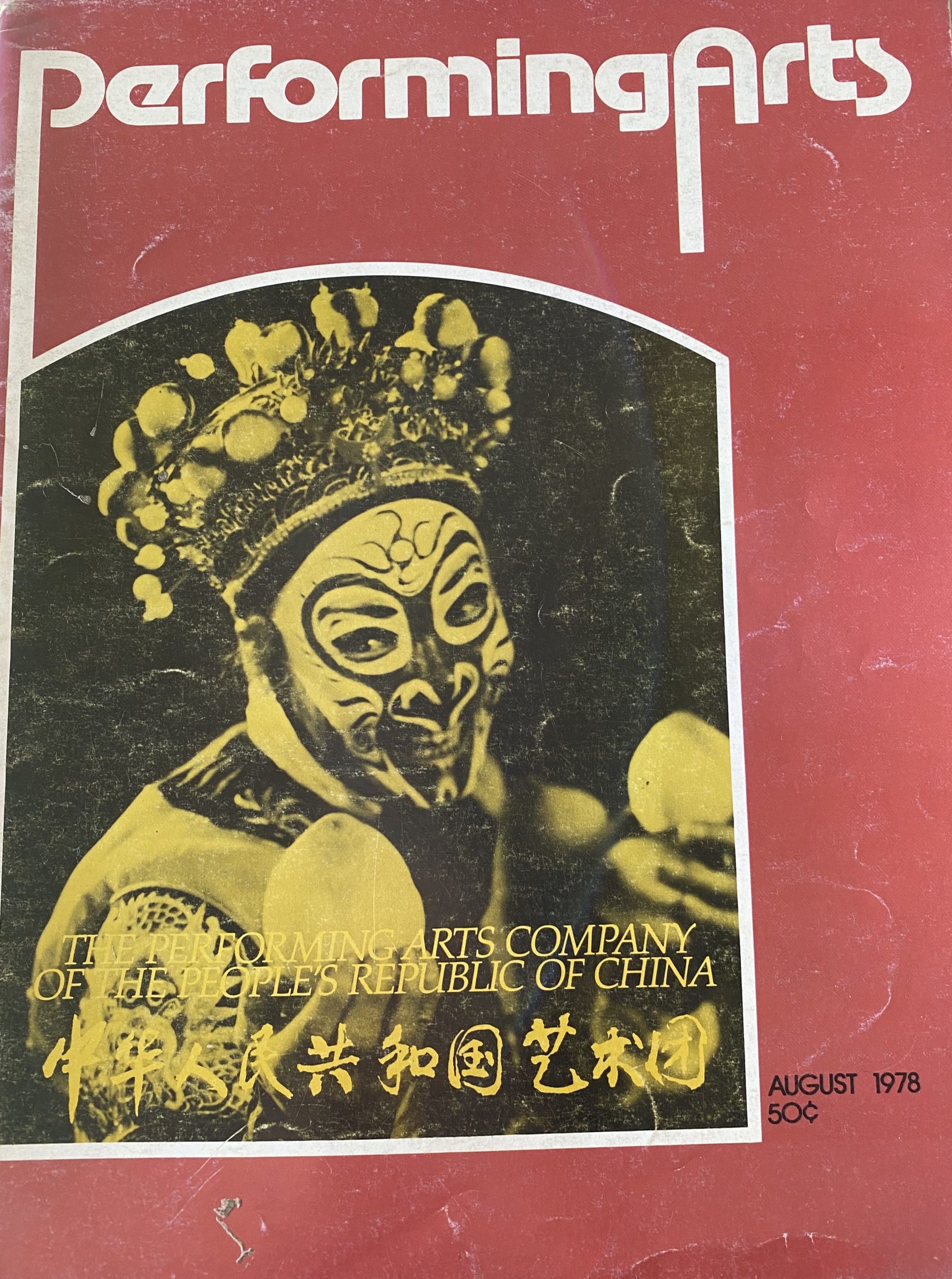

American Magazine Featuring Theater TroupeThe troupe consisted of 152 nationally selected artists–from singers, dancers, and musicians to actors, actresses, and backstage designers. My granduncle’s job was the latter, assisting the performers with costumes and face paint.

American Magazine Featuring Theater TroupeThe troupe consisted of 152 nationally selected artists–from singers, dancers, and musicians to actors, actresses, and backstage designers. My granduncle’s job was the latter, assisting the performers with costumes and face paint.

The troupe would go on to perform more than 30 performances in major cities across the country to audiences of well over one hundred thousand spectators.

Their first venue was the Metropolitan Opera House at the Lincoln Art Center, which sold out on the first day with a stellar reception. They received commendable reviews from The New York Times.

These Artist Ambassadors brought a performance that opened the door into Chinese cultural heritage .

After performances, during free days, my granduncle explored more of New York’s attractions, such as Wall Street and Niagara Falls.

Members of the Performing Arts Troupe in Washington D.C.Everything was new to my granduncle in these frenetic cities juxtaposed with his pastoral fields.

Members of the Performing Arts Troupe in Washington D.C.Everything was new to my granduncle in these frenetic cities juxtaposed with his pastoral fields.

On a visit to a homely blue-collar household in rural America, he joked that the acres of property put the Summer Palace to shame. Touring the farmhouse’s interior, he marveled at even the children had their own rooms.

In the backyard, my granduncle and team were treated to barbecue on a long picnic table. They tasted staples of American cuisine such as fried chicken, and buttered potatoes.

The troupe would continue their expedition across the U.S. to perform at local colleges and theaters. But first, they stopped by the White House to meet President Jimmy Carter.

On the Rose Garden Grounds

On the Rose Garden Grounds

Ayoung American woman had been his backstage assistant. She asked him how she could say “you’re welcome” in Chinese.

My granduncle replied, “bù kè qì.”

She then responded with “bù qì kè,” to which my granduncle smiled. He found Americans to be hard-working, and disciplined, adhering to the general opinion of Americans that the Chinese visiting art troupe had.

This comfortable, high-quality lifestyle afforded to the typical U.S. resident was anomalous to him. It would not be echoed in Beijing or other major Chinese cities until the turn of the 20th century.

For my granduncle, who maintained a 10 RMB wage, his tour of America was an eye-opening experience.

Although so much has changed industrially, technologically, and economically, some things will remain constant.

A never-ending adaptation of our human values, a mutual appreciation and investment towards each other’s cultural legacy, and the stories we tell to the younger generation.

[zombify_post]

0 Comments