Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin are integral to Chinese architectural history and preservation.

The two architects were born in the early 20th century, and almost single-handedly contributed to the field of documenting the infrastructural vestiges of a bygone era. amid

Amid the politics and ideology that characterized Republican-era China, they wielded grace and resilience as emotional armor. Their legacy has been regarded by some as complicated as the times in which they lived.

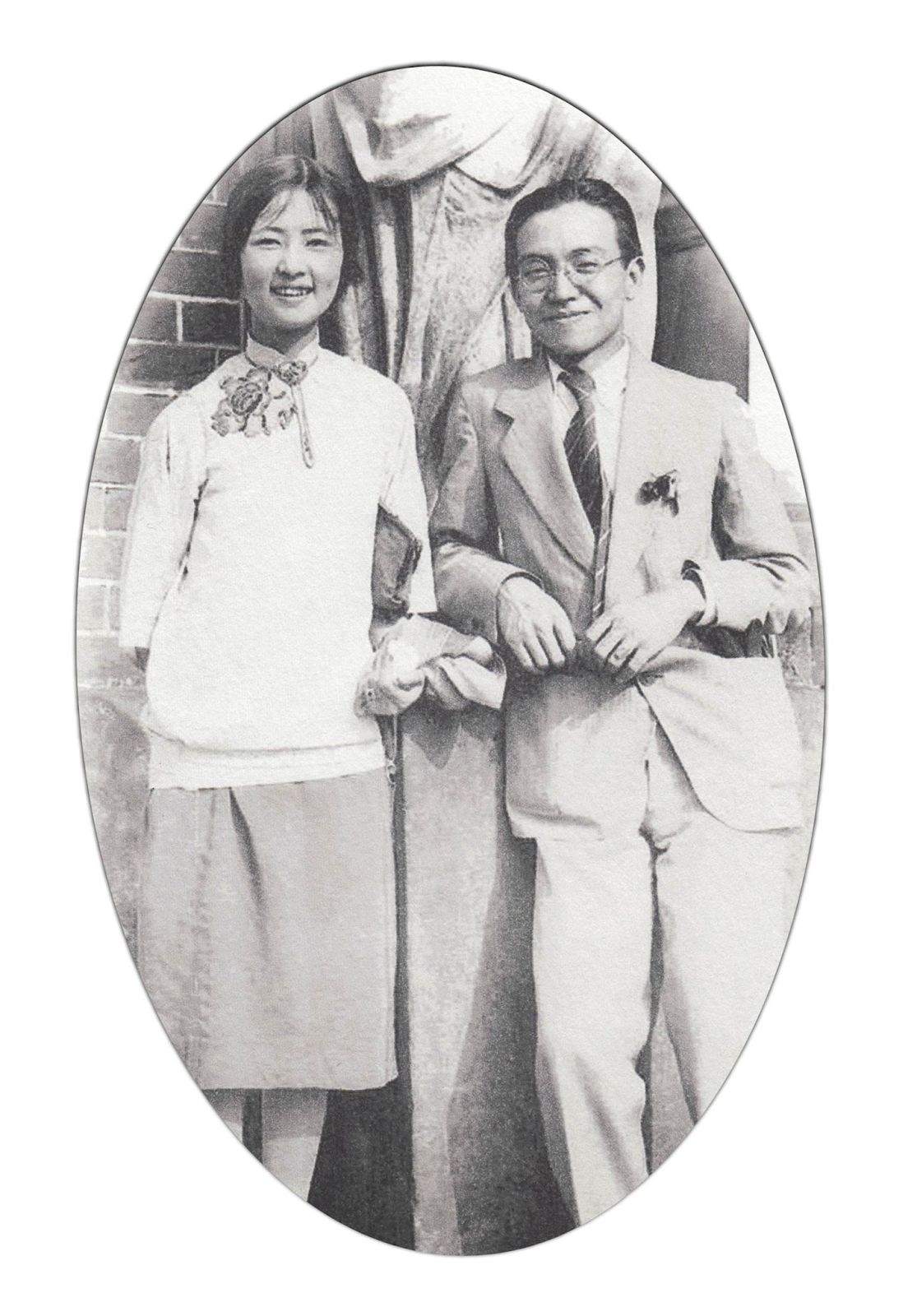

Liang and Lin

Liang and Lin

Who were they?

Liang Sicheng was the son of Liang Qichao, a revolutionary who had been exiled to Japan for his work in the Hundred Days Reform movement. This was an attempt during the waning years of the Qing dynasty to restrengthen a range of China’s social institutions including those at the educational, militaristic, and economic levels.

Aligned with a progressive attitude, his father ingrained Liang with values of classical Chinese education. But also, he emphasized the utility of expanding his horizons and learning from the West.

While enrolled at Tsinghua University, Liang learned English and drew graphics for the school newspaper. His love for drawing and meticulous temperament aided him well in his future studies and career as an architectural pioneer.

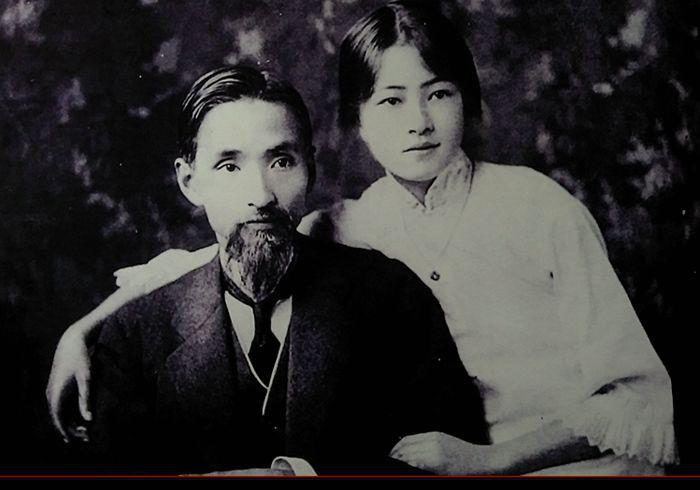

Lin Huiyin was the daughter of a powerful politician, Lin Changmin. Lin Changmin was a man equally known for his bureaucratic work as his artistic sensibilities.

At a time when education was only afforded to wealthy families, not to mention for a woman, Lin participated in intellectual activity and dialogue from an early age. In her teens, she went with her father to London and was introduced to architecture by a schoolmate.

During her sojourn there, her bilingualism was only further pronounced by the expressive language and captivating ideals portrayed by English poetry and drama.

Lin Changmin and Lin Huiyin

Lin Changmin and Lin Huiyin

Overseas Training & Application

The patriarchs of the Liang and Lin families were well acquainted, having both established respected reputations and residences in the cultural and literati hub of Beijing. Naturally, they were keen on marriage prospects for their respective “favorite” son and daughter.

Yet, it wouldn’t be until years later that the brilliant gallant and fair lady would officially wed/ They married in North America, largely due to Lin’s prompting of Liang to study architecture with her at UPenn.

To her dismay, the architecture department only admitted men. Lin instead landed a part-time teaching job, while taking classes alongside Liang.

After graduation and nuptials, the two honeymooned through Europe before arriving back in China. Drawing from a Song-era manual on timber construction, the Yingzao Fashi, by Li Jie, Liang set out to put his skills of drafting and field work to test.

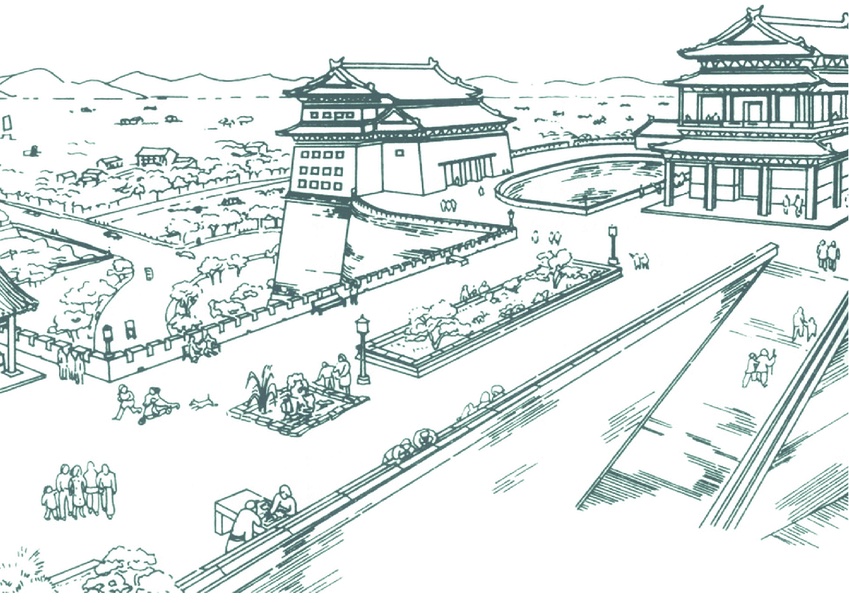

He had just gotten a post at the Institute for Research in Chinese Architecture, which was situated in a remote part of Tian An Men Square. His venture into the evolution of Chinese architecture would take him out of the comforts of palace complexes, and into the unabashed countryside.

One of the Major Halls in Longxing Temple, housing the 70ft high Thousand-Armed Thousand-Eyed Guanyin

One of the Major Halls in Longxing Temple, housing the 70ft high Thousand-Armed Thousand-Eyed Guanyin

Although these expeditions were physically taxing, the documentation of architectural structures dating back to the Tang Dynasty offered an opportunity to understand the practical applications. Examples include such as the Hall of the Buddhist Deity Guan Yin.

These expeditions also provided him with the original material and framework to his comprehensive tome, “The Collected Writings of Liang Sicheng,” as well as “Annotated Architectural Standards.”

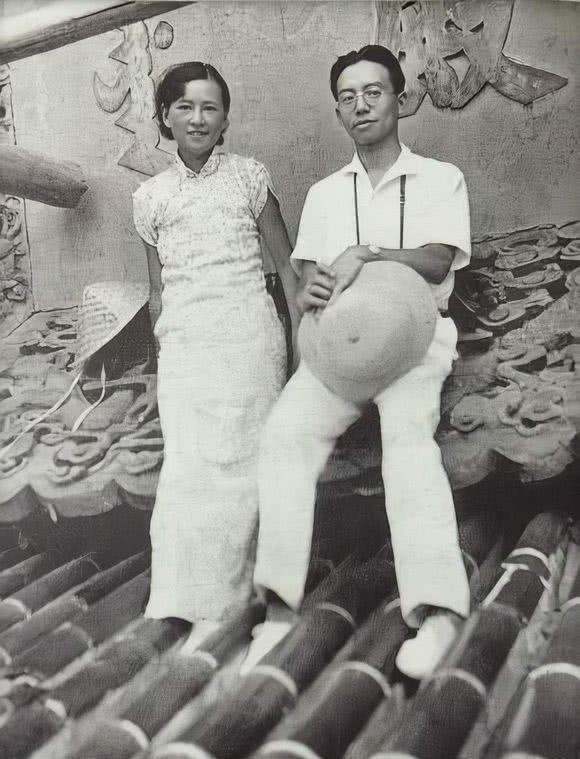

Lin sometimes accompanied Liang on his reconnaissance into the past. Liang and Lin: Partners in Exploring China’s Architectural Past, a biography written by mutual friend and Chinese art historian Wilma Fairbank, depicts the two stand on the blue ceramic tiled roof of the Temple of Heaven.

Not only is it a testament to their unwavering partnership in protecting China’s unique and treasured relics, but it illustrates quite figuratively the boldness and dynamism involved in both exploration and historical preservation.

Obstacles

During the revolutionary years, a host of inauspicious events happened that would derail Liang and Lin. A stray bullet during a political coup of Beijing killed the elder Lin, while Lin was still studying abroad.

Liang’s father died shortly after from a botched kidney operation. To make matters worse, the Japanese were encroaching following the Mukden Incident, forcing the Liangs to flee southwards towards Sichuan Province.

They eventually built the only home they ever designed together in the small town of Lizhuang, a convergence point of the lower and upper Yangtze Rivers.

Liang was to establish a new architectural institute there along with other academics. But life was hard. There was a shortage of food, running water, and neither phone, cloth, transportation, nor lighting.

For Lin, who suffered from bouts of tuberculosis, moving to the wartime capital only strained her health further. Meanwhile, prices inflated, and bombs were dropped day and night.

Lin had to support her children and a widowed mother without Sicheng, who was often in neighboring Yunnan to raise funds for research and provide for the family.

During one air raid, Lin lost her young brother in the skies of Chengdu. In a word, the war had displaced the family, forcing them into impoverished conditions, and contributing to their health decline.

When the Communist PLA took over Beijing in 1949, Liang was back at Tsinghua, working every day of the week. His physical pain from a chronic back ailment, and a disdainful government, never deterred him.

But soon, Liang’s proposal against turning Beijing into an industrial complex was spurned. The city walls and gate towers wer torn down, and with it, the cultural legacy of the Mongol, Ming, and Qing dynasties dismantled.

Liang was a target of political persecution, and had to denounce his own behavior as well as that of his father’s. What eventually struck him irreconcilably, however, was Lin’s death in 1955.

A proposal by Liang to convert Beijing’s city walls into a park. It was rejected.

A proposal by Liang to convert Beijing’s city walls into a park. It was rejected.

Literally, Liang and Lin have overcome so many obstacles to have their legacy engraved in the stepping stones of an art form clambering for resurgence.

The two minds behind this painstaking journey were merged into one, right beginning from their university days up until each other’s time was due. Of course, their mission has not been without its grief, volatility, and setbacks.

But instead of regretting the misfortune that characterized the national ethos of the better part of the Liangs’ lives, we can choose instead to remember them. We can remember an exuberant Lin, coming back from a wintry horse ride outside Chaoyang Gate in Beijing, detailing to Ms. Fairbank the plain quietude of the old thoroughfare used for grain.

Or we can picture the triumph exuded by Liang and team after Lin confirmed that a dharani pilla outside the Temple of Buddha’s Light on Mount Wutai in Shanx had been donated by a woman disciple of the spiritual leader himself.

Liang and Lin not only contributed to their country’s architectural archives, but have helped the world become aware of the influential extent of two kindred spirits.

They pushed against the pressures of a generation dominated by strife and instability, and somehow demonstrating the possibility of meeting in the middle.

A stamp issued by China’s Postal Service commemorating Liang Sicheng, Father of Modern Chinese Architecture

A stamp issued by China’s Postal Service commemorating Liang Sicheng, Father of Modern Chinese Architecture

[zombify_post]

0 Comments